Power-Q is the polished, productized version of my Ludum Dare game PoweRL. They have exactly the same mechanics, but Power-Q has about 30 extra hours of effort invested into it. Before I send it out into the world, I want to reflect upon where those 30 hours went.

Power-Q is in beta on Mac and iOS. You can get the Mac beta on itch.io, but to get the iOS beta you’ll have to email me.

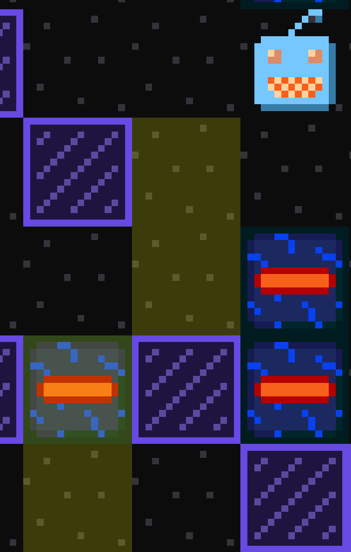

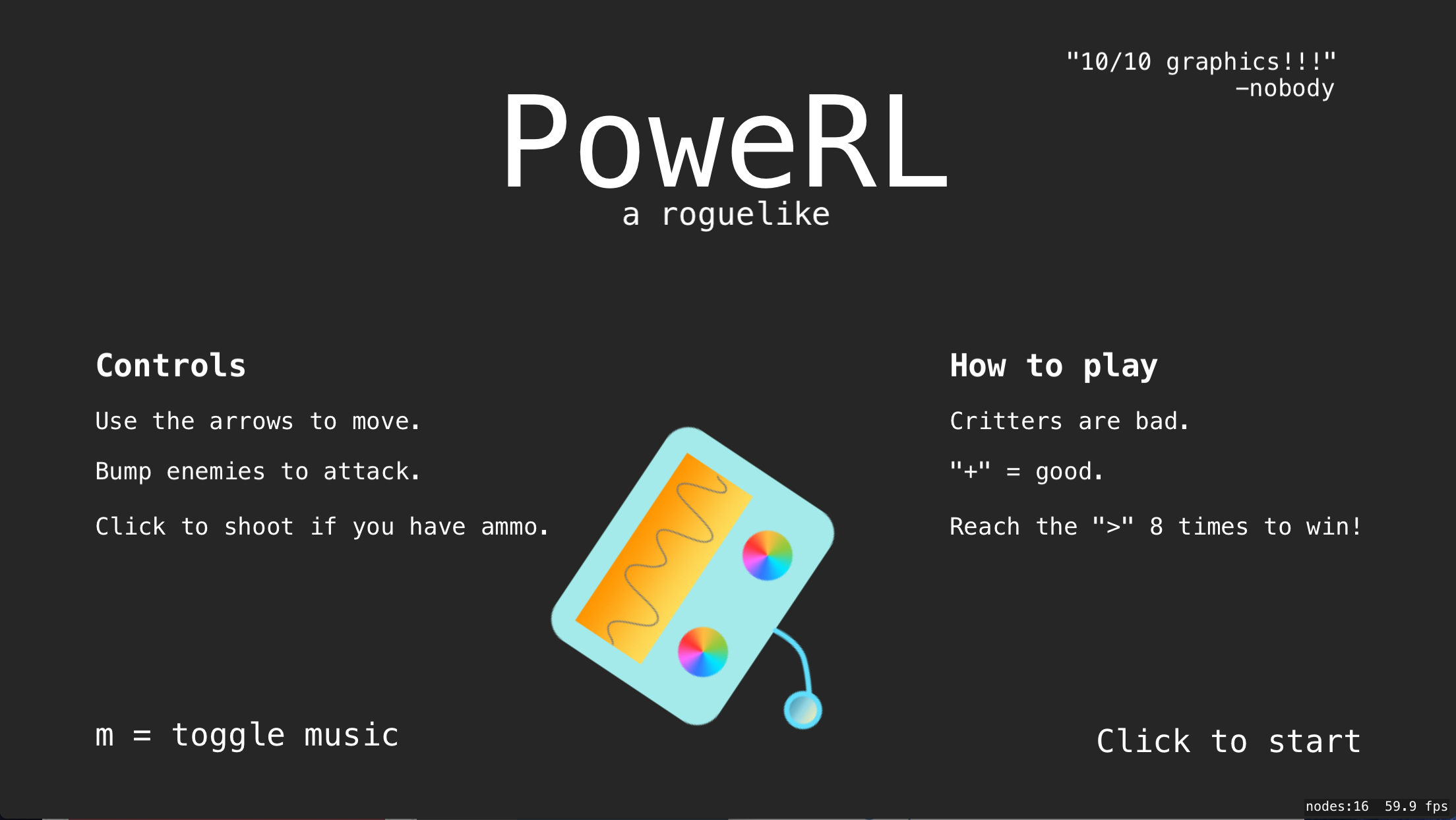

Before:

After:

Game mechanics

Power-Q is a turn-based game played on an 8-column, 6-row grid. The player is a robot with a health bar and a power meter. They can move up, down, left, or right. Each move drains power.

The level contains walls, enemies, powerups, and an exit. The overall goal of the game is to reach the exit 8 times. Each level has more enemies than the last. Powerups include health boosts, power boosts, and ammunition.

There are three kinds of enemies. They move in specific patterns (diagonals, up/down/left/right every other turn, and knight-style) and sap your health when they hit you. There are also “power drains,” which sap your power and disappear if you run over them.

The player has a melee attack and a ranged attack. The melee attack can kill a health-draining enemy in two hits. The ranged attack consumes ammunition and can kill an enemy in one hit.

Although I only published the Mac version for Ludum Dare, I wanted to make sure the interface could work on an iPhone. There are only two kinds of interactions you can have with the game: you can move (arrow keys on Mac, swipe on iOS) and shoot (click on Mac, double-tap on iOS).

That’s it, the end! That’s the whole game. Each game is supposed to last about five minutes. I could expand the enemy roster, but I wanted to limit the scope to something I could finish on weekends before my intrinsic motivation ran out.

Polishing the mechanics

I was pretty happy with the mechanics in the context of a short game, but I wanted to solve a few problems before sending it out to the masses.

Unreachable exits and powerups

One of the most common bits of negative feedback from Ludum Dare raters, besides crashes, was that the exit was sometimes unreachable or too close to the player to be a challenge.

I could have solved this by writing a smarter level generator, but I liked the general character of the levels I was getting already, so I just added a flood fill-style reachability check and had the game re-roll the level if it was no good. Exit placement was solved by putting it as far away from the player as possible instead of any old place.

If you look at the console logs, you’ll see that every level is re-rolled 1-4 times on average, but it’s really fast, so it won’t matter to players.

Frustrating targeting

Shooting follows a line determined by Bresenham’s algorithm. It means a bullet path follows the yellow squares:

The algorithm is popular and well understood. It’s convenient for a programmer, but can be frustrating for players if used for this kind of thing naïvely.

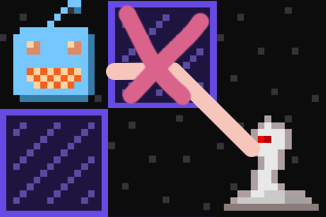

As an example, take a look at this situation:

Given the way shooting works, the player could reasonably expect to shoot around the corner. And it would work:

But what if the middle two cells were flipped? The player probably expects to be able to shoot the enemy.

Oh no! That’s a terrible experience! it will fail and the player won’t know why.

I solved this problem by exploiting the asymmetry of Bresenham’s line algorithm. If you run it from point A to point B, you get a different set of points than if you run it from point B to point A! By running it both ways every time, almost all of these weird cases are covered because the reverse version uses a slightly different path from the regular version.

Smarter enemies

The AI in this game is really dumb. The diagonal- and knight-moving enemies don’t do any pathfinding. They just move to whatever cell is closest to them.

The dumb AI is mostly fine, but for the “turtle” (originally an actual turtle, now a kind of blobby thing), which moves one cell up/down/left/right every other turn, it was too much of a limitation. So I added pathfinding just to the turtle. It will move toward the player even if it has to go around some walls, instead of getting stuck in corners like an idiot.

Scoring

Typical players will die a lot before beating the game, and I don’t want them to feel like they aren’t progressing. A simple high score counter seemed like a good solution. I made each enemy worth one point and displayed the highest score on the title screen.

Art

I developed the game using ASCII characters for most of Ludum Dare. Midway through, I turned the enemies into emoji. As the deadline approached, it didn’t feel right to use Apple’s beautiful high-resolution animal illustrations as my game art, so I did some bad tracings in Pixelmator and shipped it.

I immediately regretted all of my art choices. The whole thing looked like crap to me. So I downloaded Piskel and started on some 16x16 pixel art style sprites. The result was a lot more charming! I packaged it up into a post-compo build with some crash fixes a couple days after the jam ended.

Polishing the art

As I converted more of my art to the new style, I became frustrated with Piskel’s UI. I bought Aseprite instead and my pixel art productivity skyrocketed. I reduced my color palette and put the finishing touches on the sprites. As someone without any art training, I found creating the color palette to be a bigger challenge than I would have expected, though I suspect if I had started with Aseprite instead of Piskel I would have been more consistent from the beginning and had an easier time of it.

My game-over screens were just black voids with text in the middle of them, so as soon as I was done with the sprites, I did some simple illustrations for the three possible endgame conditions: a win, a loss due to power, and a loss due to health.

One enemy, formerly known as the turtle, moves every other turn. It was impossible to know at a glance whether it was about to move or not. I replaced the single turtle frame with a blobby thing that flips between two frames.

I’m leaving a lot out here. There were probably a hundred more little things I did to the art.

Music and sound

Music production for 48-hour game jams requires a careful balance between time spent and dopeness. My initial music pass had a pretty good set of sounds and melodies, but I rearranged it a little bit for the final release. I might still write a second track.

To get an extra push over the musical polish line, I put GooseNinja’s space-themed loading track over the title screen. If this game makes any money, I’ll be kicking some of it over to them.

My approach to sound was to open Logic Pro X and bonk around on presets until it sounded video gamey. It worked great! I didn’t change much on the sound front, but the ranged attack sound was a little clipped and unimpressive. I replaced it with two sounds: one for the player firing and one for the impact of the bullet. The firing sound is a drum machine hi hat and the impact is a kick drum.

I added graphical toggles for sound and music, because smartphone users are often listening to podcasts or music while they play games. I made sure the game wouldn’t interrupt any already-playing audio.

My Ludum Dare score for audio was a lot lower than I thought it would be, so I worry that I haven’t done enough for the audio of this game. My last game, Rogue Basement, scored much higher and didn’t even have sound effects! What it did have, though, was four tracks of music and cool location-based transitions between them. Power-Q doesn’t have the same sense of space, and I’m not sure I’ll be able to make the music as distinctive as it was in Rogue Basement no matter what I do, so I’m not worrying about it for now.

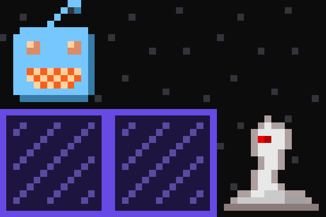

Help screen

For the Ludum Dare build, I did what most people do: slap some instruction text on the title screen. For the final version, I moved the instructions to a separate screen.

Before:

After:

Portrait mode

One of my core beliefs as an iOS gamer and developer is one that apparently isn’t shared by game developers who make otherwise great games:

If your iOS game can be played with one hand, it should support portrait mode.

I can’t believe I even have to bring this up, but for frack’s sake, 868-HACK can only be played in landscape mode! I’ve developed a comfortable but absurd grip that lets me see the screen and move, but there is absolutely no reason why that game could not let you rotate that little glass rectangle 90 degrees and keep all the text readable.

Given my passion for this belief, as soon as Ludum Dare was over, I began to think about how I’d go about supporting portrait mode in Power-Q.

In terms of just the interface, the solution was simple. The 8x6 grid was designed to comfortably fit on an iPhone 5S without scrolling, so in portrait mode, it would just become a 6x8 grid! The map would physically stay in the same place in both rotations; only your perspective of the objects would change. The resource bars and labels would be at the bottom of the screen instead of the left.

In practice, this feels a bit weird when you see the rotation in person, but when you’re playing locked in one rotation it doesn’t matter at all and just works.

But in the code, it was nightmarish. I had to move a lot of layout code around and make sure every sprite was in the right place at all times. And because the map was just rotated 90º, I also had to un-rotate all the sprites individually and do a little bit of funky coordinate space translation math to detect grid touches correctly. Now every single screen in the game has two completely separate layouts that have to be individually tested.

So I guess I lied when I said there was “no reason” why 868-HACK couldn’t support portrait mode. It would be a lot of work. But I swear on Steve Job’s grave that I would pay $10 for an in-app purchase that enables it.

Now that I’ve baked the portrait/landscape duality into the game, I think I’ll just do it for every iOS game I make going forward. The patterns are easy to understand and implement. In the future, though, I’m going to just make games with scrolling or square maps so I don’t have to rotate the playing field.

Saving and loading

Power-Q is a simple game without an explicit save system, but on iOS it’s important not to lose the player’s game when the app is kicked out of RAM.

That means my hacky, often thoughtless Ludum Dare code had to be refactored a lot. The main issue was that the map generator gave you a fully connected object graph with lots of references between objects, instead of a flat data structure that was easy to serialize.

There was no shortcut, so I just dove in. It took about 500 lines of new code, but it worked the very first time I ran it. (I have a lot of practice writing serialization code from working on Hipmunk!)

PowerRL/Power-Q uses an entity-component system. The main change I made was to add serialization code to every component possible. I also introduced new components whose only job is to hold information used to reconstruct more complex components when the game is loaded from a file.

Here’s what the save file looks like. It’s written at the beginning of each level and loaded when the app launches.

Takeaways

Swift, SpriteKit, and GameplayKit are really, really good for rapid prototyping and general 2D game development. I’ll never produce a Windows or Android port, but having fun is more important to me.

Good-looking pixel art is much easier for me to create than vector art. I’ll just start with that style in future game jams.

It helps to think about saving and loading from the beginning, to avoid working with bad assumptions about how scene construction and map creation should work.

Re-rolling bad procedurally generated levels is much simpler than writing fancy algorithms to make them good in the first place, as long as it’s cheap to do so.

Full changelog

- Completely new art in every screen

- Portrait mode supported on phones

- UI layout tweaks in every screen

- Help screen

- No levels with unreachable exits or powerups

- Music is slightly better

- Different sounds for shooting

- Game saves at the start of each level, loads on launch