With the end of a semester just past, my course projects are all bubbling up in various states of completion. One of these is a point-and-click adventure game called Space Train: Terror on the Mustachio Express, developed by a team of students from the Cleveland Institute of Art and Case Western Reserve University. Its technical components include an event-driven level scripting system, characters, items, inventory, dialogue, and more. The engine is written in Python using my game programming weapon of choice, the pyglet library. The plot:

Inga Borga is a poetry-loving senior citizen. One of her favorite authors, Stanislov Slavinsky, is reading his poetry live on the nearby Planet Deux, a short hop by space train from Inga’s home. She wants nothing more than to see Stanislav in person, so she catches the Mustachio Express to Planet Deux. Little does she know it will be a bumpy ride…

Sounds grand, right? We thought so too, but in typical student fashion we failed to account for one thing: adventure games take a lot of work to make. As a result, the game is only about twenty minutes long. Even so, we all learned from the experience.

The Course

“EECS 390 - Advanced Game Development Project” is a joint course between the Cleveland Institute of Art and Case Western Reserve University. Teams of 6-12 artists and programmers collaborate to produce some sort of game. At the end of the course, the teams present to their peers and to Electronic Arts staff for questions and critique. The course is currently taught by Dr. Marc Buchner (CWRU) and Knut Hybinette (CIA).

The other two games made this semester were Kalotai, a location-aware monster collection/battle game for Android, and Louder Than Words, a platformer with branching story lines based on a morality system.

How It Went Down

We all arrived at 8:30 AM on the first day of class, heavily caffeinated. Everyone put ideas on a white board and then divided into three teams based on interest. My team ended up with four programmers and six artists, with me as team leader. We immediately decided on some basics and began working on a schedule. By 9:45, we had drawn a crazy whiteboard diagram.

It was already clear that we would make the best game ever. The drawing was so good we didn’t even need a design document. We wrote one anyway because it was a course requirement. We spent the next month and a half developing the environments and the characters, fleshing out plot points, and writing the game engine.

The class was only scheduled to meet for an hour every week, which was far from enough time to get anything done. Most of our communication was done on Fridays in a classroom when we met to give status updates, brainstorm new directions, and work on the schedule. During the week, we communicated via a mailing list, shared files using a Dropbox shared folder, and pushed code back and forth with git.

At the halfway point, we presented our work to the class. Our demo revealed some significant issues, none of which were technical: the character art lacked a consistent style, the story was not cohesive, and there were no clear puzzle designs. The characters we did have were shallow and stereotyped. This was not a good situation to be in for a story-based and art-heavy game!

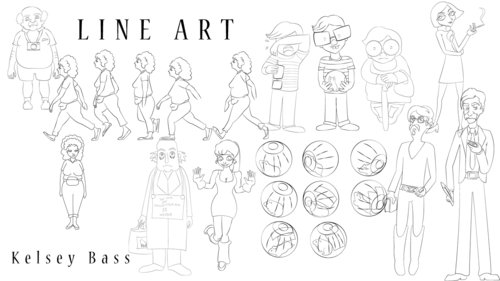

We immediately changed our art and story development processes. Rather than have three or four artists take characters all the way from concept to final execution, we split all character work into line work, coloring, and shading, and assigned one artist to each stage of the pipeline. Rather than working from a vague, error-prone shared idea of a partially-recorded story, I spent a few hours writing detailed scripts for each level we planned to implement. We followed this process to the end, and it worked beautifully. We had a very slick demo.

Here are some screenshots of the game:

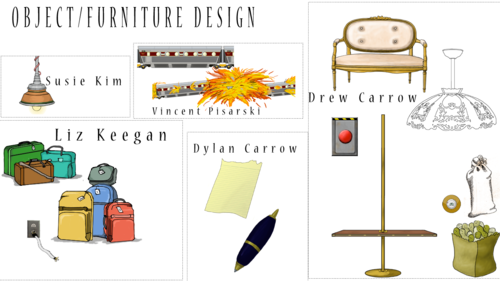

Here are some of the stages of the game’s artistic development:

Lessons Learned

I had never been in a months-long team leadership position before. My experience organizing CWRU Hacker Society helped, but that was more cat herding than game building. By the end of the course the team had worked out a process by trial and error that seemed to produce results, but by the time we found that process, it was really too late to save the game.

Schedule

We spent too much time thinking up random characters and not enough time fitting them into a big picture. We should have started writing pseudo-screenplays or storyboards to work from by the third week. That would have made it easier for us to give the artists specific tasks, a problem we had early on.

Storyboards would have given us the opportunity to implement parts of the levels, which would have helped us develop a scripting API. For most of the semester, we worked with an ad-hoc API. We ended up redesigning it in the last week because it wasn’t working for us anymore.

Adventure Games Are Hard to Make

Almost every game I have ever made has involved bullets. That usually means those bullets are heading for a relatively small number of enemy types, are flying over relatively simple pre-rendered or procedurally generated terrain, and have very simple animations. In an adventure game, everything the player sees has a unique design and multiple animations. The average screen time of a given image is minutes or less. Even though we were working with six artists, we were barely able to finish our 20 minutes of play time.

Communication is Key

We encouraged communication by providing as many useful collaboration tools as possible. Without constant communication, Space Train would have been a total failure.

By keeping all live game assets in a shared Dropbox folder, we guaranteed instant availability of the artists’ work without using a cumbersome email system or an artist-unfriendly version control system. Our consistent meeting format was usually effective at giving everyone concrete goals for the week. Git, of course, is the ideal code collaboration tool. The mailing list filled in any gaps.

Course Project Group Dynamics are Weird

I’ve always felt uncomfortable with the way course project groups are formed. Usually they form around ideas, not around teams, and that was explicitly the case with this course. This means that team dynamics are a total crapshoot, and if things go south, you’re locked in for three months and your success is irrevocably chained together. By the end of the course, we effectively had two programmers and four artists, with four other people functioning as dead weight.

Conspicuously Absent From This List:

Significant code issues. We really powered through the engine and never got hindered by any major design flaws. The game’s source code is on Github. It’s not beautiful, but it worked well enough for us.

The Team

- Steve Johnson: Lead programmer, screenplay, music, engine, UI

- Kelsey Bass: Lead artist, character design/line work/animation

- Fred Hatfull: Level scripting, engine, UI

- Liz Keegan: Environments, objects

- Tyler Goeringer: Level scripting, engine

- Susie Kim: Objects

- Drew Carrow: Character design, environment/objects

- Sean Murphy: Sound, pause screen

- Dylan Carrow: Coloring, objects

- Vincent Pizarski: Character design, coloring, exteriors

Kelsey did caricatures of the team for the credit sequence. Here’s mine for: